Browsing with a desktop screen reader

Posted on by Henny Swan in User experience

In our first post from our browsing with assistive technologies series, we discuss desktop screen readers.

You can also explore browsing with a mobile screen reader, browsing with a keyboard, browsing with screen magnification and browsing with speech recognition.

A screen reader is a software application that announces what is on screen to people who cannot see, or who cannot understand, what is displayed visually. They provide access to the entire operating system and applications including browsers and web content.

Who uses a screen reader

People who are blind or partially sighted use a screen reader, as well as people with cognitive or learning disabilities who find it helpful to listen to what's on screen instead of look at it.

People who are blind and read Braille may use a screen reader in combination with a refreshable Braille display. A refreshable Braille display is an external piece of hardware made up of rows of pins that can be formed into the shape of a Braille character. People can use Braille in combination with speech output or without it. Braille displays are a useful tool if people are in meetings or in a noisy room where listening to the speech output is not convenient.

Some screen readers also support screen magnification. This enables people with low vision to use a combination of speech and sight. The magnifier enlarges content while the reader announces everything on the computer screen, echoing typing and automatically reading documents, web pages, and other applications.

Popular desktop screen readers

There are a number of desktop screen readers people can choose from. Windows has Narrator built in and macOS has VoiceOver.

VoiceOver is the only screen reader available on macOS, but there are other screen readers that can be installed on Windows, including NVDA and JAWS.

Orca is the screen reader for Linux distributions that use the GNOME desktop.

According to the WebAIM Survey of screen reader users in 2021 the most popular screen readers are JAWS or NVDA on Windows and VoiceOver on macOS. Chrome is the most commonly used browser with Microsoft Edge usage increasing.

It is not uncommon for people to have two desktop screen readers. Windows users might use JAWS at work and NVDA at home, because although JAWS is expensive it's often favoured by employers, where NVDA is free. People who use Windows at work may prefer to use macOS at home, meaning they use JAWS at work and VoiceOver at home.

What desktop screen readers announce

When it comes to web content, desktop screen readers will read everything on a web page, provided it has been coded correctly, plus some things that are not visible.

All text is read out including paragraphs of text, headings, lists and form labels.

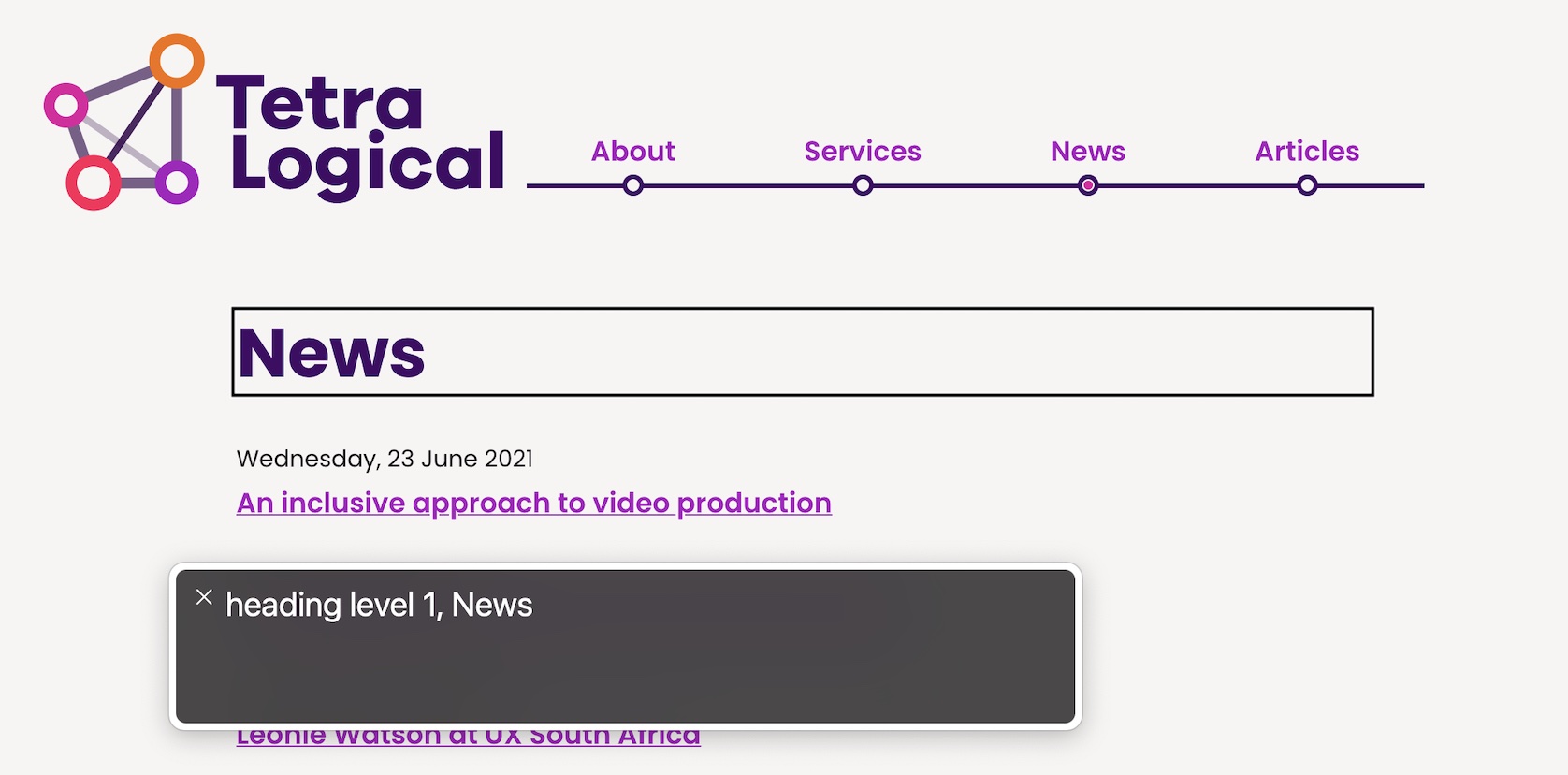

Screen readers also announce useful information about the content, based on the HTML elements that have been used. For example, when a screen reader encounters a heading that uses the <h1> element, it announces the element's role as well as the heading level. The "News" heading in the screenshot below would be announced as "Heading level one, News" where "heading" is the role and "one" is the level.

When reading lists screen readers will announce how many items are in the list and when the end of the list is reached. For example, "List of 3 items, 2 of 3" or "End of list".

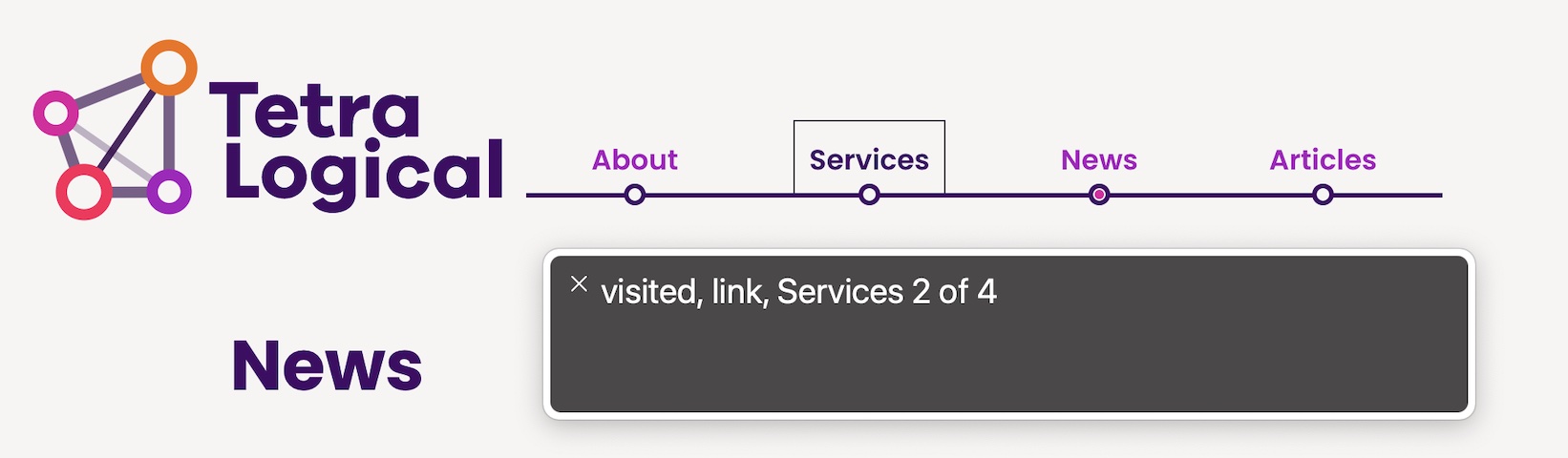

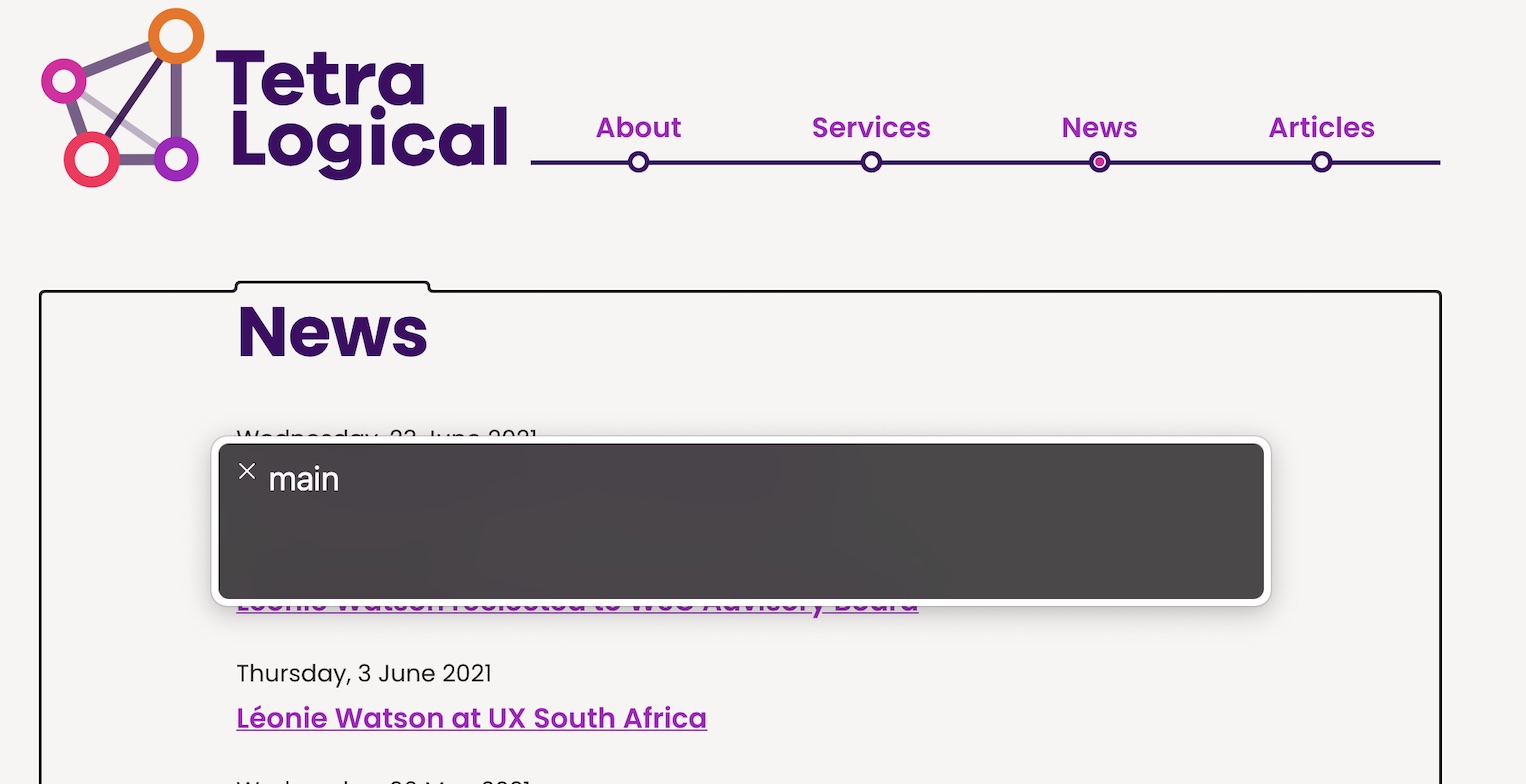

Working in partnership with the browser, screen readers are able to identify almost every kind of HTML element, including those used to represent tables, forms, images, links, and landmark regions like navigation blocks or the main content area of the page.

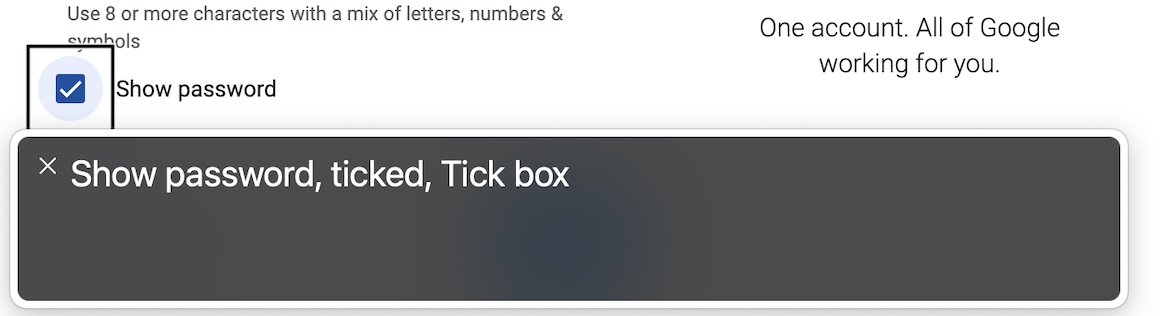

Like headings and lists, when navigating elements such as links, buttons or form inputs, screen readers announce the text content as well as the role and state of the element. For example, a button with the visible text submit will be announced as "Submit, button". A checkbox that is selected will be announced as "checkbox, selected" or "checkbox, Checked".

Note: Screen readers all do the same things, but they do not always do them in exactly the same way. For example, one screen reader might announce "image" and another "graphic", when they encounter an <img> element. These differences are to be expected and are nothing to worry about.

Screen readers also announce hidden text like text descriptions for images, or content that has been intentionally hidden from sighted people.

Navigating with desktop screen readers

Where sighted people will visually scan a page, then make decisions about where to navigate or what to concentrate on, screen reader users will do the same but with keyboard commands.

While screen readers often have different keyboard commands, people tend to use the same general strategy for exploring, navigating, and reading content.

When opening a web page, screen readers will automatically read the page from top to bottom, starting with the page title. However, it's common for people to stop the screen reader, then explore the content for themselves.

British Sign Language (BSL) version of "Browsing with a desktop screen reader"

Standard keyboard navigation

The Tab key is used to navigate to the next focusable element such as links, buttons or form inputs. To move backwards Shift + Tab is used.

Enter is used to activate links and Enter or Spacebar to activate buttons. The Arrow keys are used to navigate static content such as text as well as interact with components such as menus, tab panels, sliders and so on.

Use of the Tab, Shift + Tab, Enter and Spacebar keyboard commands is the same for people navigating a web page with a keyboard but this is where the similarity ends. The difference between keyboard and screen reader navigation is that screen reader users have many more keyboard commands available to them.

Screen reader navigation

A common strategy is to scan a page using headings or landmark regions, then use other keyboard commands to explore relevant content in more detail.

This enables people to understand the overall structure of content, before deciding what to do next. For example, a screen reader user may navigate between the headings on the page until they find one that seems to preface the content they're looking for, then they'll use more keyboard commands to read the subsequent content, activate a link, or perform some other task.

Navigating by headings is very common amongst people who use screen readers, 85.7% of respondents in the 2020 WebAIM screen reader user survey reported heading levels as key to navigating pages. This is in contrast to only 25.6% of respondents reporting navigating by landmarks as useful.

This could be for any number of reasons such as landmark regions not being implemented as well as headings by developers. Or possibly people being less familiar with landmark regions.

When a screen reader user finds the general content they're interested in, they have many different options to choose from, including:

- Reading content by character, word, sentence, or paragraph

- Reading all the content from there to the bottom of the page

- Navigating between links

- Completing forms

- Navigating data tables

Skip links

Skip links provide a way for keyboard users to bypass repeated content, including main navigation and search, and jump to the main part of the page, but they're not always used by screen reader users.

According to the 2021 WebAIM screen reader user survey, skip link usage among screen reader users is mixed with only 16.8% reporting they always used them and 14.4% reporting they never use them.

Screen reader verbosity settings

All screen readers can be customised to suit people's preferences. Verbosity settings determine how much detail screen readers will read back. This might include announcing text formatting changes, punctuation, and information about components such as tables or frames.

How much people customise a screen reader will vary depending on preference, familiarity, and experience.

Speech rate

Probably the most common setting people change is the rate of speech output.

Many people who use screen readers on a daily basis listen to the speech output very fast. This is similar to how someone who is sighted might skim read and read fast in their head. The speech rate can be so fast that output is almost impossible to follow for people unaccustomed to screen readers. This is why it is important to prioritise keywords first in links, headings and sentences.

Punctuation

Another common setting is the amount of punctuation spoken. Screen readers all treat punctuation a little differently by default, but they can all be configured to the user's preferences.

A common choice is for the screen reader to speak punctuation just like a person would if they were reading out loud. This means that most punctuation is not actually spoken, but is inferred from the way the screen reader speaks - a brief pause for a comma, a slightly longer pause for a full stop, or a rise in inflection for a sentence that ends with a question mark for example. Only a few punctuation marks are actually spoken - the @ sign in an email address or the forward slashes in a web address for example.

It's tempting to try and write content that is announced in a particular way by screen readers, but writing content that works well with screen readers is a remarkably complex task.

Summary

People use desktop screen readers because they cannot see the screen, or because they have a cognitive or learning disability that means listening to content is helpful.

People who use desktop screen readers have many keyboard commands at their disposal. These commands are used in various combinations depending on what the user wants to do - read a section of content, scan a page for a section of interest, find out how a word is spelt, activate a link or button, and more besides.

Desktop screen readers are dependent on the quality of the code that was used to create the application or the web content. If the wrong HTML elements are used, the screen reader has no way of identifying what the content is, and the screen reader user has no information to help them make decisions about what to do with it.

Next steps

Read an inclusive approach to video production to learn more about how to produce accessible video and how our embedded accessibility service can help you achieve sustainable accessibility.

Updated Thursday 2 March 2023.

We like to listen

Wherever you are in your accessibility journey, get in touch if you have a project or idea.